International Brigade Memorial Trust

By Geoffrey Billett

The invitation of Alfredo González-Ruibal to venture down an archaeologist’s rabbit hole, into a dimension of reverse-engineered history, is surely appropriate for the journey he and his colleagues have made, both this year and last.

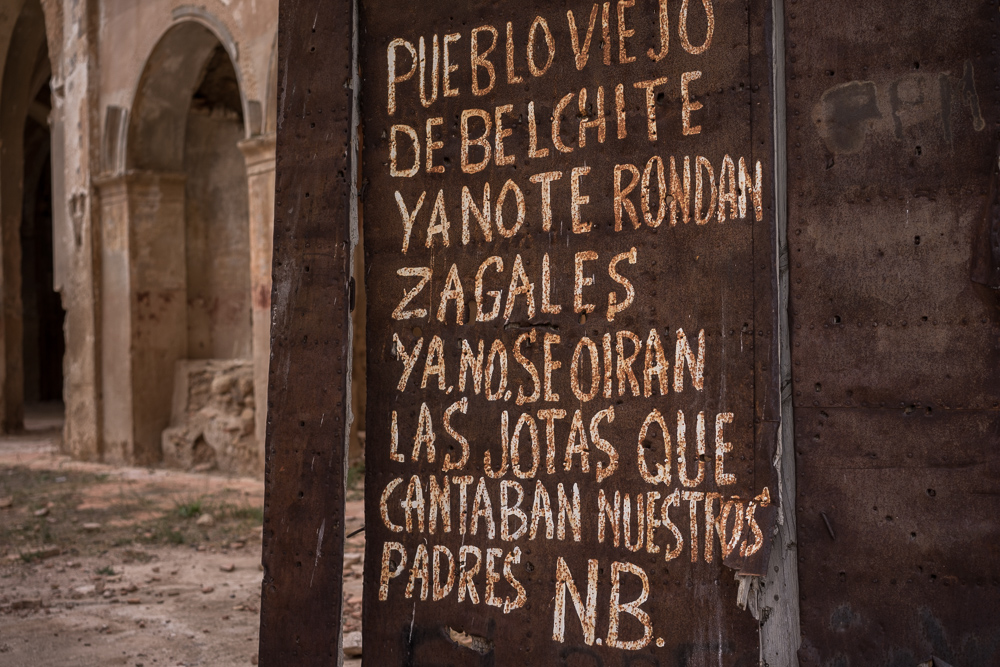

Belchite, a town in the northern Spanish province of Zaragoza, still feels the ghost of General Francisco Franco, in the wind and within the decaying ruins of a town ordered by Franco to remain as a ‘living’ memorial, after its total destruction in the Spanish Civil War. Alfredo has returned for two consecutive years to do battle with this singular ghost, assembling his own army of like-minded archaeologists, anthropologists and volunteers.

Forty years after his death, Franco’s ghost town still casts a shadow over the new town, built by the defeated and captured Republican soldiers of the second Republican government, in place of the shattered original. Its reformation began as their progressive values, belief systems and personal constitutions were systematically degraded by forced labour, inadequate nourishment, political suppression, and constant fear of death.

Separated by a single road, the new town has been described as a ‘fascist’ design of straight roads, and an uninspiring, inorganic grid system. There is no mistaking the scrawny, elongated angels perched on the minaret-tower of the mudejar church at the town centre, or the yoke and arrows (el yugo y las flechas) insignia high on a wall opposite – both are incontrovertible signs of the right-wing Falange movement, which Franco ideologically identified with.

In 2015, the digger rumbles across the scrubby grass and lifts buckets of earth, revealing the original soil walls and gravelly bottom of a trench from 80 years before.

In this trench, Nationalist soldiers – and later, Republican soldiers – fought and died. Archaeologists scrape and dig to unearth as closely as possible its original contours and design. Down the slope towards the Seminary, more workers dig to unearth the latrine of what is considered a concentration camp.

Situated between missing marian statues of the Virgen of Lourdes and Pilar of Zaragoza, it had once been a garden where trainee Catholic priests could seek solitude; now the repetitive clang of trowel on stone provides an alternative spiritual experience in the September sun.

High above both the latrines and the trench, a pill-box on a further promontory is being assessed; the digger will be needed to remove all of the rocks dumped into it by successive farmers, obscuring where the machine gun was once nested.

This landscape of conflict remains a battleground, where the metaphysical archaeological concepts of materiality and ephemerality are the main conceptual weapons of today’s soldiers and freedom fighters. Young intellectuals try to make sense of – and undo – a wrong which stubbornly, at least in Spain, remains unyielding to science or reason.

Alfredo himself discusses the concept of anamnesis, describing an inner knowledge of things which we do not know we have – a knowledge base which is instinctive, accumulative and develops into a form of higher empathy where artefacts found convey an emotional story-board of both an individual’s inner and societal constructs.

He describes being able to use this accumulation of knowledge to sense the emotionality of the person whose possessions have been found, and to further understand the liminal environments explored, almost like finding and understanding strands of DNA.

Little red flags across the soil denote the position of finds; bullets, cartridges and clips, all rusting and decayed, popping out of the impacted earth like grubs amongst the ants and black beetles which share their terrain. Alfredo can tell their origin; Russia Mosin or Mexico for the republican bullets and Germany Mauser for the nationalists.

The Republican ordinance is older, from another generation, less predictable, more unreliable – but they both cause death. The thin metal casings of early grenades, as dangerous to their carriers as to the intended enemy, are fragments scattered like a constellation of rusty stars upon the ground.

Kneeling and scraping away in this alien landscape, the world subjectively changes; we are in the environment of soldiers and militia men, a dimension where carefully constructed patriotic illusions of sacrifice to god and country slowly refocus into a reality of fear and panic, of men firing blindly towards an enemy they perhaps cannot see but know in another time as brothers and fellow countrymen.

Rusting sardine tins, the broken light blue glass of medicine bottles, the sharp metal of barbed wire, a small metal button which has become dislodged, a crucifix fallen from a neck, a leather heel from a boot, glass from a bottle of cologne to make a soldier smell less like death – all provide some light for the shadows, material culture for the archaeologists to work and reconstruct with.

The old town is now surrounded by a perimeter fence; the crumbling church towers of San Martín de Tours and San Agustín rise above the petrified landscape where many thousands died in 1938.

A potential mass grave site has been found, secrets are being uncovered, and those still remaining are demanding the attention of a young generation of Spanish people asking questions about their country’s past. The systematic trans-generational destruction of progressive thinking and freedoms from 1939 to 1975 require light to rinse away the residual darkness.

The brooding ghost town of old Belchite and its crumbling glory is sometimes the site of film sets (Pan’s Labyrinth, The Adventures of Baron Munchausen) and has recently welcomed tourists to learn of its history, with three guided tours provided daily.

Perhaps this exposure is a metaphor for more widespread progress into understanding and countering the darkness of oppression, evidence that the ghosts of Franco can be exorcised one by one, and proof that returning to where we have never been is more a reality than a dream.

More information on the International Brigades Archaeological Project can be found here.

Words and pictures by Geoffrey Billett. This article first appeared on bizarreculture.com on 6 October 2015; reproduced by permission. See http://bizarreculture.com/the-ruins-of-belchite-ghostly-reminder-of-the-spanish-civil-war