International Brigade Memorial Trust

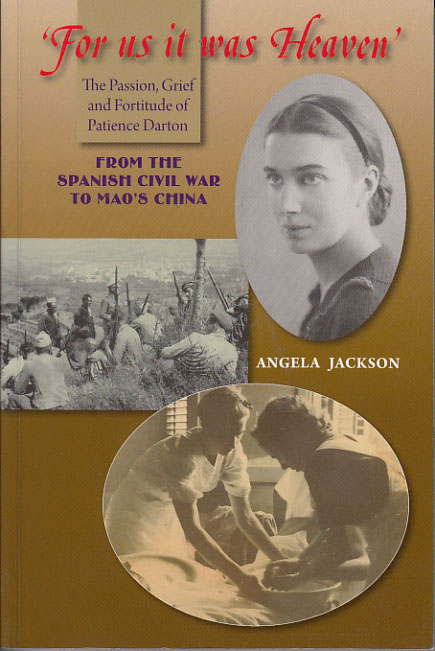

NEARLY twenty years ago, Angela Jackson, then beginning the research for her doctorate, conducted an interview with a woman who, many years before, had worked as a nurse in Republican Spain during the civil war. The story that Angela was told that day by her eighty year old interviewee, Patience Edney (née Darton), became an important part of a ground-breaking thesis. It also led to a well-received book which, like this one, was published within the Cañada Blanch series on contemporary Spain.

The publication of this biography of Patience thus brings Angela back to her beginnings and, perhaps understandably, is the cause of a certain amount of reflection by the author. In many ways the book is a personal account of Angela’s relationship with Patience and the process of researching and writing. As the author acknowledges, it is not always an easy task to write about someone that you are close to, requiring the ability to ‘tread carefully the path between hagiography and hatchet job.’ This, in the main, the author manages well, despite her obvious affection for her subject.

The opening chapters portray Patience in the years before Spain, where we learn about the development of two important and long-standing features of Patience’s life: nursing and left-wing politics. Born into an upper middle-class family, Patience decided to train as a midwifery nurse at University College Hospital in London, where she was also introduced to progressive politics by the illustrious scientist and dedicated Communist, J.B.S. Haldane.

The story of Patience’s time in Spain naturally forms the central part of Angela’s portrayal, for Spain always had a strong hold on Patience’s heart. She had been training when the Spanish Civil War broke out and was persuaded to go out to Spain to nurse the British Battalion’s former commander, Tom Wintringham, who was dangerously ill with typhoid. As anyone who has read Angela’s Jackson’s previous works will know, a nurse’s life in war-torn Spain was not an easy one and this biography presents a clear picture of the impossible conditions under which the Republican services were forced to operate, where hospitals and ambulances were deliberately targeted by the Nationalists. Yet, despite the long hours and near exhaustion, there was still the opportunity for love and it is here that Angela’s close relationship with the subject allows us particular insight into Patience’s life in Spain. Uncovered through her personal letters, we hear how she fell in love with and married a young German International Brigader. Soon we realise why Angela refers to Patience’s grief and her fortitude: her new husband was killed on the Ebro in the summer of 1938. Patience didn’t mention him again, nor did she visit Spain, for another sixty years.

In the 1950s, following the Second World War, Patience turned her efforts towards Mao’s China, carrying on the work she had begun in Spain. While there are accounts by other Spanish veterans who went on to work in China, such as Nan Green and David Crook, this is not an area that has been widely written about, so I found this section particularly interesting.

The concluding chapters return the story to Spain. In 1986 Patience attended the huge Homanaje in Madrid, accompanied by her son, Bob, named after her German former husband. The book’s last act is genuinely moving, for Patience did not survive her triumphant return to Spain: To Die in Madrid’, read Patience’s obituary in El Periódico. In a last salute to Spain, Freiheit!, the song of the German Thaelmann volunteers, was sung at Patience’s funeral. It is a fitting conclusion, both to her extraordinary life and to this engaging biography.

Richard Baxell.

This review originally appeared in the IBMT newsletter, issue 32, Spring-Summer 2012, p.10.