International Brigade Memorial Trust

Nancy Wallach, board member of our US-based sister organisation ALBA, writes about her father, Lincoln Brigader Hy Wallach, and the chess club he coordinated among fellow volunteers while held in the San Pedro de Cardeña prison. This is an edited version of a piece originally published on The Volunteer website on 1 August 2021 available here.

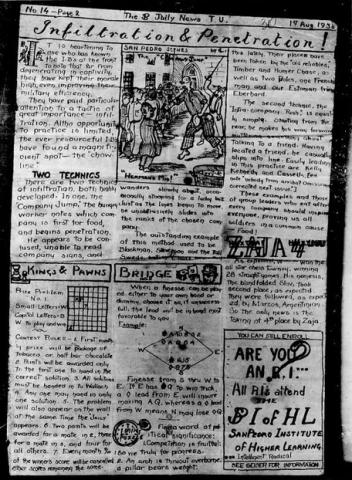

The Jaily News, August 1938, featuring the regular chess column Kings and Pawns.

‘A prominent competitive [chess] player in the United States gave a series of lectures and played over famous games from the past. To hear him talking – in our squalid surroundings – with such knowledge about a game once played by Napoleon on the island of St. Helena, was an uplifting and inspiring experience.’ This is how George Wheeler, a young British Battalion volunteer recalled, in his memoir ‘To Make the People Sing Again’, a series of lectures given by my father, Hy Wallach, at ‘The University of San Pedro’.

The ‘University’ was part of an education programme created by the International Brigade prisoners at the fascist concentration camp San Pedro de Cardeña in Burgos. Clive Branson, who had a painting accepted by the Tate Gallery while imprisoned there, lectured on art. Frank Ryan, the commander of the Connolly Column, gave an account of the Easter Rebellion in Ireland. A German prisoner, the head of the Red Front Fighter’s Bund, whose identity was protected as a Swede named ‘Karlson’, spoke about the anti-fascist activity that had gone on in Germany before Hitler came to power.

These activities would not have been even remotely possible when the concentration camp for the International Brigade prisoners was first established. (The fascists broke their precedent of executing captured volunteers in order to work out an exchange for Mussolini’s Italian soldiers captured by the Republican side.) Chess played a large role in helping the prisoners get to the point where they could organise and ameliorate their conditions, hold these classes, maintain their morale and even publish an underground newspaper. Chess could not change what the Spanish historians Javier Bandres and Rafael Llavona have described as ‘infrahuman living conditions, a preview of Dachau or Buchenwald.’ As British volunteer Dave Goodman described: ‘It was grim. No windows, just bars. It was cold. There was a stone floor and no bedding. Sanitation was minimal. You’d get a very small loaf of bread once a day, otherwise only beans’. Chess did help the prisoners to resist the constant efforts of their fascist captors to degrade, demoralise, and dehumanise them. It kept their spirits and convictions unbroken.

When my father was captured in April 1938 he recalled: ‘In San Pedro, we were faced with miserable conditions, beatings and fascist propaganda. We thought it was necessary to have a functioning Communist Party in order to counteract these conditions in an organised way … and to keep alive the spirit and purpose we came for – to continue our struggle against fascism. Initially, we were not allowed to get together or even speak. But we met under the guise of a chess club…We helped to organise the San Pedro University. We created a newspaper, the Jaily News, edited by Sidney Rosenblatt, Bob Steck and myself…’ my father recalled. The Jaily News would counteract the lies of the fascist press, the only papers they were officially allowed to read.

It was in the quiet of the ‘chess club’, sliding messages under the pieces, that they established the policies of protecting the officers and German volunteers, and of giving only the briefest information when interrogated so that their statements could not be used for fascist propaganda. They determined that no prisoner in the camp was to admit to a rank higher than private, as the fascist policy was to execute any ranking officers. In addition to protecting the identity of their officers they also felt it was important to protect the identity of the Germans who were captured. The Gestapo often visited the camp in pursuit of these German antifascists who, if detected, would have been executed or sent back to Germany to be tortured in their camps.

My father was most proud of the way the ‘chess club’ helped to organise the prisoners to resist the pressure of the fascist authorities and to get them to renounce the Republic and their reasons for coming to Spain. ‘We were required to respond to the questionnaires issued to us by the fascists,’ he recalled. ‘Overwhelmingly, the prisoners reasserted that we had come to Spain to fight against fascism.’

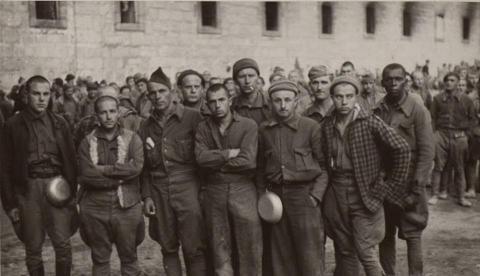

Lincoln Battalion prisoners photographed in San Pedro de Cardeña, including George Delich (third from left), Carl Geiser (behind Delich) and Hy Wallach (middle), April 1938.

Chess also served as an international language which broke down the national barriers and isolation, as they held truly international tournaments and exhibitions. On the day of the escape of six Germans, my father recalled, ‘there was a chess match between America and Europe. One of these Germans was on the European team. On the day of this escape, there was no inkling. He seemed so concerned about the match, checking with me on who he was playing the next day.’

Chess served as not only a means to meet and organise, but became an important part of the camp life, helping to take one’s mind off the hunger, filth and constant barrage of beatings. It reminded these half-starved, lice-infested prisoners of their humanity, intellect and spirit, which their fascist captors constantly sought to break down.

Perhaps one of the best examples of this was related by Lincoln Brigader Carl Geiser. In his book ‘Prisoners of the Good Fight’, he points out that chess not only lifted the spirits of the prisoners but for a moment even brought out the humanity in their sadistic fascist guard, Tanky, who once interrupted a chess activity in which my father, standing in the centre, was playing about 30 people simultaneously. As Tanky walked in, swinging his club, they expected him to disrupt the games, smashing the pieces to the floor and flogging anyone who could not escape the arc of his club. They reassured him they were not up to some subversive activity and explained that my father was playing everyone at once. ‘Tanky was dumbfounded,’ Carl wrote. ‘He had never heard of such a thing…He slapped his thighs, unabashedly showing his astonishment. I must give him credit for being human enough not to break up our chess games that day.’

It is interesting to learn about some similar interactions with chess by prisoners in a maximum-security prison in Spoletto, Italy in 2015. Mirko Trascetti, who volunteered to teach these prisoners chess, writes, ‘When you are in jail, days seem endless and every second turns into an eternity. To these new players, chess became a way to break the routine, to keep their mind away from the place they were in.’ A prisoner confided to him, ‘While I was focused on the game,...I could distract myself and take a break from the problems and the thoughts that obsess a prisoner.’ ‘Chess,” Trascetti concluded, ‘eased the pain he was feeling because of the distance that divided him from his family.’ Some 83 years ago, chess played that same role for the International Brigaders in the fascist prison of San Pedro de Cardeña in Burgos.

Posted on 15 April 2022.