International Brigade Memorial Trust

Spain, July 1936: from uprising to civil war

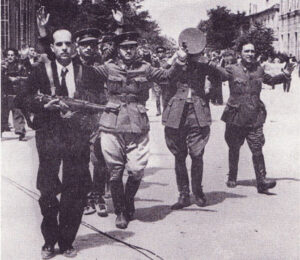

Rebel officers captured during the uprising

In July 1936 a military rising was launched in Spain by a group of military generals aiming to overthrow the Republican government, elected only five months previously. Though initially successful in many parts of Spain, opponents of the rising- working people, trade-unionists, members of political organisations from the centre to the left and, in some cases, members of the Civil Guard and the new Republican police force, the Assault Guard- took to the streets, erected barricades, and confronted the insurgents.

Faced with determined opposition the generals saw that their rising was in real danger of being defeated. With their best soldiers, the elite Army of Africa commanded by General Francisco Franco, trapped in Morocco, the Rebels turned to fascist Italy and Nazi Germany for assistance. After some initial hesitation, both Hitler and Mussolini sent help to the Rebels, crucially providing aircraft to ferry the Army of Africa across the strait of Gibraltar onto the peninsular. Once across the strait, the Army of Africa rapidly headed north, leaving a trail of slaughter and destruction in their wake. Within weeks Franco's forces were approaching Madrid, where they united with the rebel army of the north, led by General Mola.

Desperate pleas by the Spanish Republican government for assistance from the European democracies of Britain and France fell, overwhelmingly, on deaf ears. Terrified of the prospect of a wider European conflagration, and convinced that appeasement of Germany and Italy was the best means of preventing it, the European powers chose not to intervene, nor even to provide military support to the Republican government. Instead, an agreement was made not to intervene in the conflict, to which Britain, France, Germany Italy, Portugal and the USSR all agreed to adhere. However, it quickly became apparent that the agreement strongly favoured the Rebels, who continued to receive assistance from Germany and Italy, despite the non-intervention agreement.

Appalled at the prospect of another European country succumbing to fascism, supporters of the Spanish Republicans government from around the world flocked to its aid. To these anti-fascists, Spain was the latest battleground in the European war against fascism, and Spain offered a chance to, at last, to check its advance. At the same time, the Comintern and the USSR, fully aware of the extent of German and Italian assistance to the Rebels, chose to provide help to the Republicans. In addition to the military help sent from the USSR, the Comintern (the Communist International) took on the role of organising the volunteers for the Spanish Republic, many of whom had already arrived in Spain. Over the coming months, these International Brigades of foreign volunteers would fight and die alongside the Spanish Republicans in their determination not to let the fascists pass. Madrid, its defenders declared, 'would be the tomb of fascism'.

FURTHER READING

Raymond Carr ed., The Republic and the Civil War in Spain, London: Macmillan, 1971.

Helen Graham, The Spanish Civil War. A Very Short Introduction, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Paul Preston, A Concise History of the Spanish Civil War, London: Fontana, 1996.

Hugh Thomas, The Spanish Civil War, London: Eyre and Spottiswoode, 1961.

There is a huge literature in English on the Spanish Civil War. For a excellent overview, see the bibliographical essay in Paul Preston's book, listed above.